Introduction

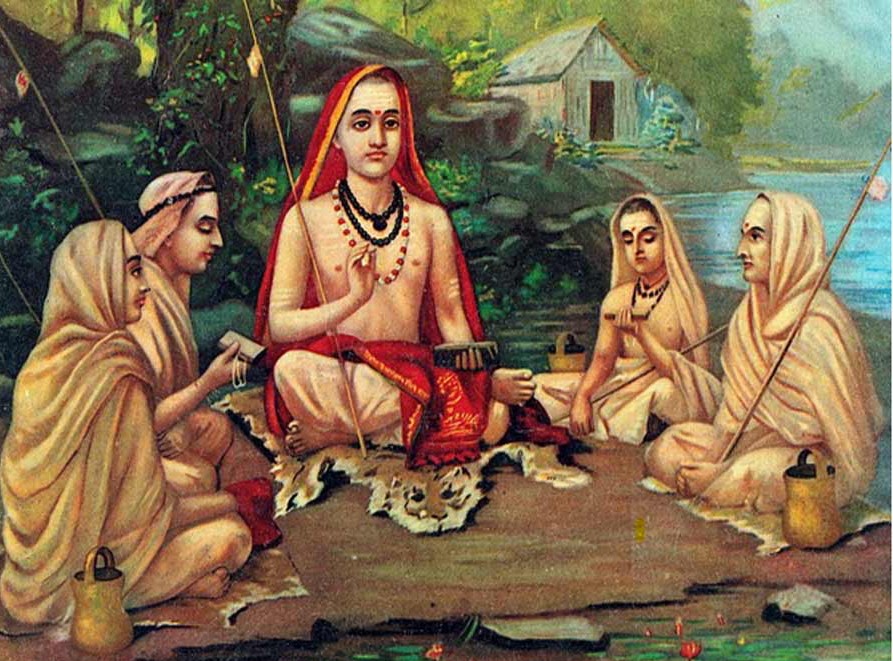

The Upanishads are considered some of the most profound texts in human history. They are part of the Vedas, making up the philosophical section. As they form the concluding section of the Vedas, they are considered as Vedanta (the end of the Vedas). The term Upanishad literally means “sitting near” and is based on the Guru-Shishya tradition, where a seeker of wisdom sits near a wise teacher.

Unlike other sections of the Vedas, the Upanishads have a unique focus that makes them universal and valuable for all. They emphasise spiritual philosophy and meditation, largely ignoring the Vedic rituals and procedures known as Karma Kanda. This inward-looking approach, with its emphasis on meditation as the most important aspect of life and the exploration of different states of consciousness, makes the Upanishads timeless and ever-relevant.

First, I need to discuss a subtle yet profound difference between the philosophical approaches of the Upanishads (and other ancient Sanatan Dharma philosophies) and Western philosophies. The Sanskrit word for philosophy is Darshana, which is associated with seeing, whereas major Western philosophies are based on thinking. Thus, the wisdom of the Upanishads is based on the experiences of seers, encouraging readers to experience it themselves.

The Upanishads are believed to have been written over a broad period, with significant variance in dating. There are 108 Upanishads in total, with ten considered primary (Mukhya) Upanishads. These ten are particularly special due to the extensive commentary by Adi Guru Shankaracharya.

Before summarising the ten major Upanishads, I must admit my limitations in knowledge. This is my third reading of the Upanishads, and each time I discover more than before, highlighting how much I have yet to learn. My readings are based on the English translation by Eknath Easwaran, and I understand some information is always inevitably lost in translation. Hopefully, someday I will learn Sanskrit to read these ancient texts in their original form.

Isha Upanishad

The Isha Upanishad discusses Brahman, the supreme reality. The word Isha means God, referring to Brahman as the ultimate deity. It describes the infinite, eternal nature of Brahman, present in all beings. The same Brahman present in all creatures is also within us as our Self (Atman). That way, those who see all creatures in themselves and themselves in all know no fear. Also, since everything is made up of something already present in us, it advises us to covet nothing, renounce, and enjoy life.

Katha Upanishad

The Katha Upanishad features the most famous story in the Upanishads, involving a young boy named Nachiketa and the Lord of Death, Yama. The story addresses the profound question of what happens after death. Yama, the ultimate knower of death, reveals the truth about the Self to Nachiketa after he rejects all worldly pleasures in exchange for this knowledge. Yama explains that the Atman, the eternal, immortal self, never dies and is distinct from the perishable body. Realising this Self allows one to escape the cycle of death.

Yama provides techniques to realise the Self, emphasising meditation and the necessity of extreme restraint. He stresses the importance of controlling the senses and mind, as those who succumb to sensory pleasures fail to meditate and realise the immortal Self, remaining bound to the cycle of Samsara.

Yama uses the analogy of a chariot: the Self is the chariot’s lord, the intellect is the charioteer, the mind is the reins, the senses are the horses, and the external world is the road. If one cannot control the intellect (charioteer) and mind (reins), the senses (horses) will pursue sensory pleasures, leading the chariot astray. This analogy illustrates the importance of controlling the senses, mind, and intellect, with Yoga being the complete stillness where one realises the Unitive state.

After learning the techniques of meditation from Yama, Nachiketa realises the Self within him and attains immortality.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad

Brihad means great, and Aranyaka means forest. Thus, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad translates to “Great Forest Upanishad.” It is considered one of the longest and most profound Upanishads.

It begins with the story of Sage Yajnavalkya and his wife Maitreyi. As Yajnavalkya prepares to leave his wife to live as a recluse, Maitreyi, overwhelmed with sorrow, asks him about the Self. Yajnavalkya explains if we realise that everyone shares the same Self and recognise that Self within ourselves, all sadness borne out of separation (whether through parting ways, ending relationships, or the death of loved ones) will naturally dissipate.

Another story involves Yajnavalkya, King Janaka, and other renowned sages like Gargi. Gargi questions Yajnavalkya about the ultimate, imperishable truth, eventually declaring him the knower of Brahman. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad offers profound wisdom on desires, stating, “You are what your deep, driving desire is. As your desire is, so is your will. As your will is, so is your deed. As your deed is, so is your destiny.” Our desires at the time of death determine our next life, but those free from desires realise Brahman and attain true freedom.

This Upanishad also contains one of the four great statements of all Upanishads, known as Maha-Vakyas: “Aham Brahmasmi,” meaning “I am Brahman.” (Remember Sacred Games?)

Chandogya Upanishad

In Sanskrit, the word Chanda is associated with music or sound. Therefore, the Chandogya Upanishad discusses the most special sound in Hinduism, OM. It states that of all speeches in the world, the essence is the Rig Veda, and that the Sama Veda is the essence of the Rig Veda, with OM being the essence of the Sama Veda. Thus, those who meditate on OM can fulfill all their desires.

This Upanishad explains that the universe originates from, exists in, and returns to Brahman. It uses the analogy of clay: how understanding one clump of clay helps us understand all objects made of clay, regardless of their shape or form. Similarly, knowing our inner Self helps us comprehend the entire universe, as everything is made of the same Brahman.

Among its many stories is one about Narada and Indra. Narada, despite reading all scriptures, cannot realise Brahman, as all worldly knowledge is finite while Brahman is infinite. He learns that the only way to realise the infinite is through meditation, beyond intellect. Another story features Indra, who seeks knowledge of the Self from Prajapati. After meditating for 32 years, Indra initially thinks the Self is the body. Realising the flaw in this understanding (as the body is ever-changing and perishable), he returns and meditates for another 32 years, believing the Self to be the dream state. Again finding this flawed (as the dream state is subject to pleasure and pain), he meditates for another 32 years, this time viewing the Self as the dreamless sleep state. Realising this is also incorrect (as the state of unawareness cannot be the Self), he meditates for 5 more years and finally understands that the Self is beyond all three states. Hence, it is commonly said that even Indra had to meditate for 101 years to know the secret of the Self.

The Chandogya Upanishad contains one of the four Maha-Vakyas: “Tat Tvam Asi,” meaning “That you are.”

Mundaka Upanishad

The Mundaka Upanishad distinguishes between higher and lower knowledge. It considers all scriptural knowledge, like the Vedas, rituals, arts, and astronomy, as lower knowledge. The only higher knowledge is the knowledge of the Self. It warns against the perils of mere rituals, which can lead to pride and delusion, trapping people in the cycle of Samsara. It emphasises that rituals alone, like pouring butter into a fire, cannot lead to Self-realisation.

Intelligent sages, recognising the futility of mere scriptures and rituals, sought higher knowledge through meditation and ego abolition. By controlling their senses and mind and eliminating their ego, they discovered the Self. The ultimate goal in life is to realise this higher knowledge.

Mandukya Upanishad

The Mandukya Upanishad, the shortest of the major Upanishads, is considered the clearest. It describes the four states of consciousness:

- First State (Vaishvanara): Outwardly directed senses, aware of the external world.

- Second State (Taijasa): Inwardly directed senses, experiencing past deeds and present desires in the dream state.

- Third State (Pragya): Dreamless sleep state, where there is no sense of “I” or separation from the Self, yet there is unawareness.

- Fourth State (Turiya): The ultimate fourth state (Turiya means fourth), beyond the first three, where one realises the Self as Brahman.

The Upanishad links these four states with the sacred sound OM, composed of A, U, and M. A corresponds to the first state, U to the second, M to the third, and the combined sound (OM) corresponds to the unitive Turiya state, where one realises the Self as Brahman.

The Mandukya Upanishad also includes one of the four Maha-Vakyas: “Ayamatma Brahma,” meaning “This Atman is Brahman.”

Kena Upanishad

Kena means “by whom” in Sanskrit. The Kena Upanishad explains how the Self is behind the functioning of the senses, mind, and intellect by concluding that “whom” refers to the Self. It begins by questioning what makes the tongue speak, eyes see, mind think, and intellect discern, and then reveals that the Self is the one that does it all.

It then describes the Self as beyond the senses, mind, and intellect. To illustrate this, it extends the same question-answer format: that which makes the tongue speak but cannot be spoken by the tongue, that which makes the mind think but cannot be thought by the mind. It states that the Self can be realised only when one rises above the senses, mind, and intellect through meditation and understands the separation from the Self.

In classic Upanishadic style, the same concept is explained through a story. It narrates how the gods, after defeating demons, boast about their victory as their own doing. To teach them a lesson, Brahman challenges these gods in disguise. Agni (the fire god) fails to light a fire, Vayu (the wind god) fails to blow, and Indra (the king of gods) finally realises that it is Brahman behind all actions in the universe.

Prashna Upanishad

The word Prashna means question, and in the Prashna Upanishad, we encounter questions in the form of a story about Sage Pipalada and his six seeker students who ask him questions about the universe.

Pipalada begins by explaining the creation of the universe and how all duality and forms emerge from unity. He discusses two primal dualities: Prana (life force) and Rayi (matter). He explains that all dualities, like male and female or sun and moon, are created from Prana and Rayi. Furthermore, all forms and names in the universe are variations of these two dualities, which themselves come from unity.

The Upanishad details Prana, the life force running all vital functions of the body, from senses to sex. This leads to the ultimate question: where does Prana come from? Pipalada then explains that even Prana and Rayi come from the Self and that all actions in the universe are done by the Self. He uses the analogy of a bird resting in a tree to explain how the body, senses, and mind rest on the Self in dreamless sleep.

Finally, just as a river loses its name and form when it merges with the sea, all names and forms in the universe disappear when the Self is realised.

Taittiriya Upanishad

The Taittiriya Upanishad emphasises the universality of Upanishadic wisdom, explaining at length the importance of food. It teaches that food is the source of everything and lays down four important principles regarding food: always respect food, do not waste food, increase the production of food, and donate food to others in need.

It then discusses the important concept of the Five Sheaths, known as Pancha Kosas:

- Annamaya Kosha (Food Sheath): The gross, physical body.

- Pranamaya Kosha (Vital Sheath): The life force (Prana), with breath and other vital functions.

- Manomaya Kosha (Mental Sheath): All thoughts, emotions, and other mental activities.

- Vijnanamaya Kosha (Wisdom Sheath): All intellect-related discernment, logic, and higher-level intuition.

- Anandamaya Kosha (Blissful Sheath): The inner joy we experience.

Understanding these sheaths is crucial in meditation, showcasing how it is an inner journey from the physical body to the inner sheaths. The true Self, the ultimate bliss state, is beyond all these sheaths. To experience this, one needs to go inward through these sheaths progressively. In typical Upanishadic style, it tells a story between Sage Bhrigu and his father Varuna to explain these sheaths. After deep meditation, Bhrigu initially associates the Self with each sheath, from the Food Sheath to the Blissful Sheath, eventually realising the true nature of the Self beyond all sheaths.

The Taittiriya Upanishad also discusses the origin of fear, explaining that fear arises from the sense of separation from others. Those who realise their Self, and that the same Self resides in all, are at home everywhere, free from fear, and live in permanent joy.

Lastly, it attempts the seemingly impossible task of quantifying infinity for easier understanding. To explain the infinite joy of Brahman, it uses the finite metric of the joy of a young, healthy, strong man with all the wealth in the world. It states that 100 times that joy is the joy of a particular Loka (Indra Loka), and that 100 times of that again is the joy of another Loka (Brihaspati Loka), with the ultimate bliss of Brahman being beyond multiple hundreds of these joys.

(Note: I like to see these Lokas as different states of consciousness. Many of these states are limited and transient, like Indra Loka and Deva Loka, while Brahman represents the ultimate state of pure consciousness that is infinite and permanent. Also, Indra Loka could be the state of consciousness arising from heavenly sensory pleasure, as the word Indriya means sense organs.)

Aitareya Upanishad

The Aitareya Upanishad begins with a creation story, explaining how the universe originates from the Self and how all matter and beings are created from it. It then narrates another intriguing story about the creation of humans. In this story, different entities in the universe contribute to the making of a human, which can be interpreted as metaphors. For example, the Sun becomes the speech of humans and enters the mouth, air becomes the sense of smell and enters the nose, and plants become hair and enter the skin.

Amidst these metaphors, profound wisdom about the Self is revealed, considered by many to be among the most important teachings in all the Upanishads. Once every entity has entered a human body and it appears complete, the Self asks, “Where do I reside here?” It then enters as Consciousness, present in all three states (waking, dreaming, and dreamless sleep) and realised in the Fourth state (Turiya).

Everything, whether it is the five elements (air, water, earth, fire, space), living beings, or gods, is Pure Consciousness, and this Pure Consciousness is Brahman. Those who realise this Brahman live in joy and go beyond death. This way, the Aitareya Upanishad contains the remaining one of the four Maha-Vakyas of the Upanishads: “Pragyanam Brahma,” meaning “Consciousness is Brahman.”

My Takeaway

The Upanishads are considered by many to be the purest form of knowledge available. Praised for their succinct form, this same feature can also be a bug, as the Upanishads can be difficult to understand. Despite the captivating stories, the Upanishads are relatively esoteric. To ensure this wisdom is conveyed in a condensed and accessible manner to the masses, the essence of the Upanishads was told again, in perhaps the greatest story of all. That story has become the most popular book in Hinduism, which I will summarise next. (Yes, you guessed it right!)

But remember, as the Upanishads themselves say, all this knowledge has only one goal: to motivate us to experience it on our own. Otherwise, these are just mere words, and all borrowed knowledge is lower knowledge. In my own case, the Upanishads played a significant role when I first read them three years ago. Even though I didn’t understand A LOT of concepts then, they inspired me to finally dare a 10-day Vipassana meditation retreat, which I had been postponing (or prevaricating) up until then.

Leave a comment